How is talent distributed in elite cricket? Bell curve (ie. normal distribution), or something else? Here I’ll argue that the distribution of ability is the tail of a normal distribution. The evidence is strong at county level, but rather weaker for Test cricket. As you’ll see, I’ve not let that stop me.

1. Marathon Running & County Cricket

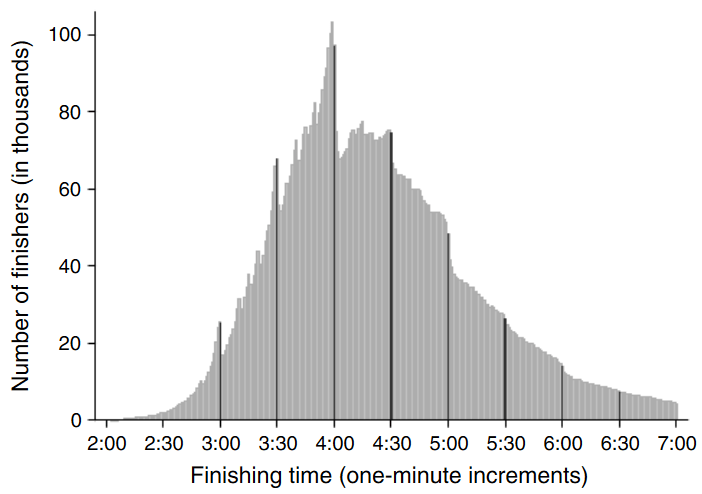

Let’s start with a different sport. Here’s the distribution of running performances for millions of marathon runners:

The spread of marathon times across the population is broadly a bell curve, but there are some subtleties: firstly, that the unfit are less likely to take up long distance running (myself included), so the distribution is lopsided. Secondly, marathon runners appear to have target times, and performances are bunched around times like four hours.

Focus on the distribution of the elite – the quicker the time, the fewer runners are capable of it. Lots of runners at the bottom of the elite pile, then fewer and fewer as the pace goes up.

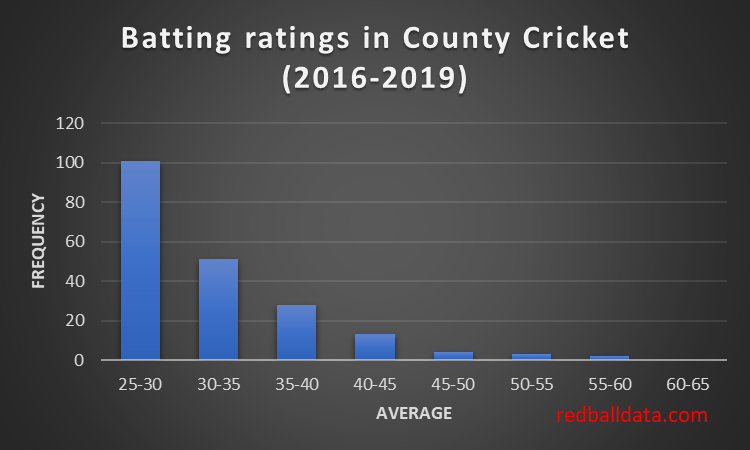

County cricket fits that pattern (based on my ratings of how players across 2nd XI and the County Championship would fare in Division 1). Loads of quite talented players who could just about make the grade, whittled down to 22 who would average over 40.

2. Test Cricket

Fans of Occam’s razor might want to look away now. This section sees me building a house on sand.

My previous post demonstrated that averages are a function of luck and talent. We know the impact of luck, we have the actual averages. Thus we can work backwards to estimate the distribution of batting talent. I’ll now suggest a distribution of batting ability in Test cricket.

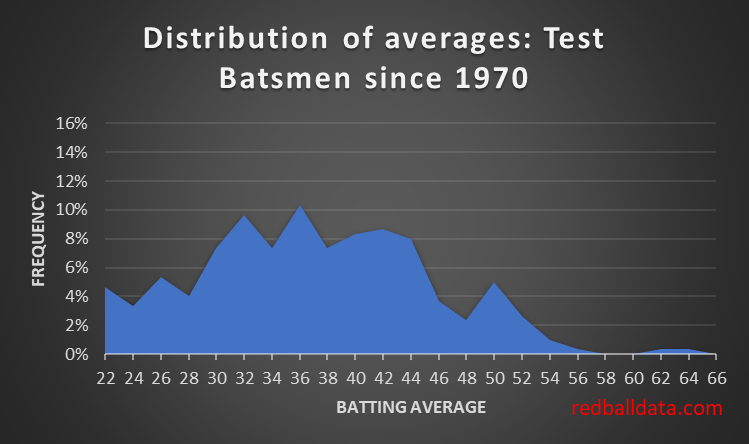

We start by making a graph of the averages of batsmen in Test Cricket. Looks a teensy bit like a bell curve, and nothing like the County chart. There’s only 300 players so it’s not a smooth distribution.

a. Talent Distribution in Test Cricket

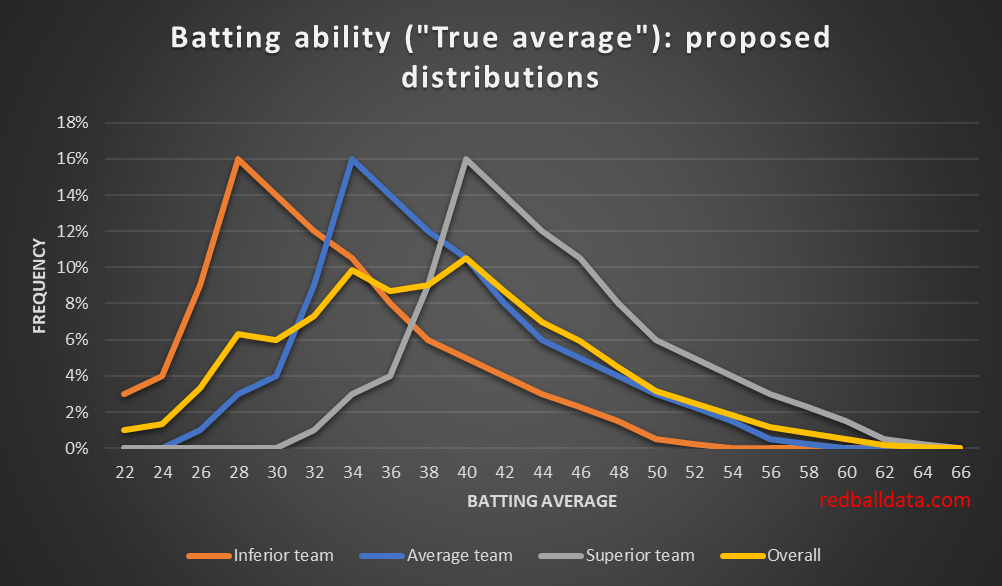

However, selection isn’t perfect. Nor is there a continuous supply of Test standard cricketers in each country. This means a sprinkling of selections who are of a lower standard. Also, each country is a different standard. This means the true distribution of Test batting ability is the sum of the curves for each country.

Putting all that together, the distribution takes the form:

That yellow curve is probably smoother in the real world. Still, not terrible as a first attempt at answering the question “what does the distribution of Test batting talent over the last 50 years look like”?

b. The Luck Curve

The median player had 75 completed innings, so I’ve used that to derive the spread in averages (versus “true” averages). A reminder: this comes from a simulation of many careers.

Strictly, I should merge many luck curves – a tight one for Tendulkar (292 dismissals, a wide one for Moin Khan (26 dismissals). Still, every journey starts with a single step.

c. Talent * Luck = Performance

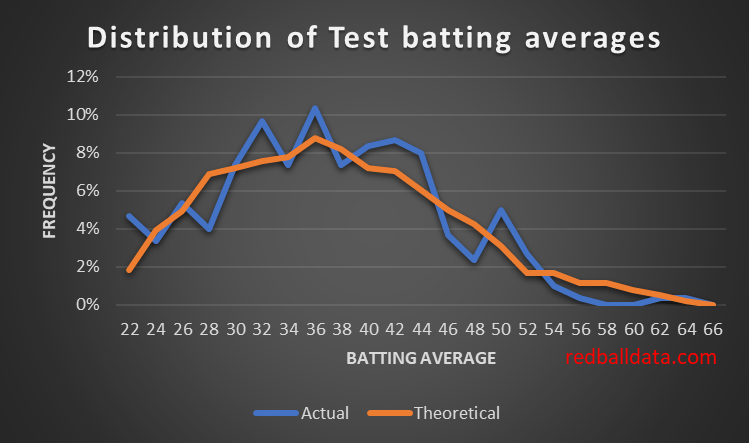

We now combine the Talent and Luck curves (probability densities) and compare them to the observed distribution

Not a bad fit. Naturally, the Actual (blue) curve is noisy as there are only 300 players that meet the criteria for inclusion. There are fewer players with very high averages than the talent curve I’ve derived would indicate – implying the real talent curve drops off more steeply than mine.

Discussion

What use is knowing how talented players are (rather than just knowing how well they performed)? In order to judge if a player has been unlucky or is unsuited to Test cricket, one needs to know the level of talent they need to have.

If you feel uneasy about the hand-waving approach I’ve applied here, then don’t worry – because so do I. Tinkering to make one curve look like another (noisy) curve is not the most rigorous analysis I’ve done. Just take away the message that luck plays a big role in averages, and we can’t yet use numbers to know how talented Test batsmen really are.

Further reading

Always worth seeing if someone has asked this question in baseball. Here’s analysis that finds batting ability would be normally distributed if you assume fielding is 30% of the value of a player. I can’t comment on baseball, but for cricket that figure is too high. Thus it’s an interesting technique, but not contradictory to my curves. If one could quantify the value of fielding (and/or other attributes) for top order batsman, then the approach in the linked piece could be replicated.

***

*Since 1970, batting in the top six, min 20 matches

I’m not sure that 30% is too high for fielding.

Ran the numbers a while back and found that the average Test batsman is dismissed in 62 balls, though that includes being dropped about a quarter of the time ( turned down LBWs add to the effect but are unquantifiable). This effectively brings their average balls faced to about 56, assuming perfect fielding.

Hence the number of runs they would score would also drop, with higher SR batsmen dropping more than lower. Add in the turned down LBWs, potential runouts, missed stumpings etc and you are likely looking at about 50 balls. The fielding value of this probably tops 20%.

Though then you have either poor or catastrophic fielding which allows unearned runs through, relieves pressure or forces a captain to move a fielder back. Likely worth a few %.

So I could make a quantifiable case for somewhere between 20 and 25%. Though the demoralising factor will itself be significant for the fielding side, along with the boost for the batsman. 30% overall really isn’t unreasonable.

Long / short, Paul Collingwood is the best Test player we have produced over the last 30 years.

Talking of baseball fielding watching flat 80-100 yard throws in that game rather reminds me of the oldest athletic world record, that of throwing a cricket ball 140 yards 2 feet. Durham had a competition many moons back and the longes throw was less than 90 if memory serves. There’s some good arms out there but… nothing on the average American baseball player. I doubt they rip their arms to shreds for no good reason.

LikeLike

I think there’s a difference between cricket at baseball in that throwing is very visible, and there’s nowhere to hide. Cricket has slips for those that can’t throw, fine leg for those that can’t catch, or mid-on if you can’t do either.

Once saw an overseas pro after a club game throw from one side of the ground to the other, reckon that was 90+ yards. But agree cricket has some catching up to do, it’s just that catching is a more important skill than throwing distance.

LikeLiked by 3 people

All very true. I imagine baseballs a a bit easier to throw too and their fielders are all in front of the bat.

The problem with quantifying fielding is that all runs are not equal, though we often pretend that they are. Say you had to choose between an opening bat who averaged 35 and one who averaged 40. The former is a brilliant slip fielder who catches 95% of chances whilst the latter is a good / average slip fielder who catches 80%? I’d think the press would be clamouring for the latter whilst the former is statistically the clearly best choice.

The interesting question is how low would you go for the former?

Similar scenario for a fast outfielder who will get to and catch more chances, which wouldn’t even be evident for a lesser fielder who wouldn’t get to within 10 yards of them ( and therefore wouldn’t be thought of as chances at all).

Has anyone tried to quantify the compound interest accrued from good catching and fielding?

LikeLike